Christopher Alexander was no ordinary architect — he was a visionary who reshaped the way we think about the spaces we inhabit. Born in 1936 in Vienna and raised in England, Alexander studied mathematics and architecture at Cambridge and Harvard, spending much of his career at the University of California, Berkeley. His interdisciplinary background allowed him to approach architecture from a unique, analytical perspective, blending his mathematical training with a deep philosophical interest in design and seeing his work used across multiple fields.

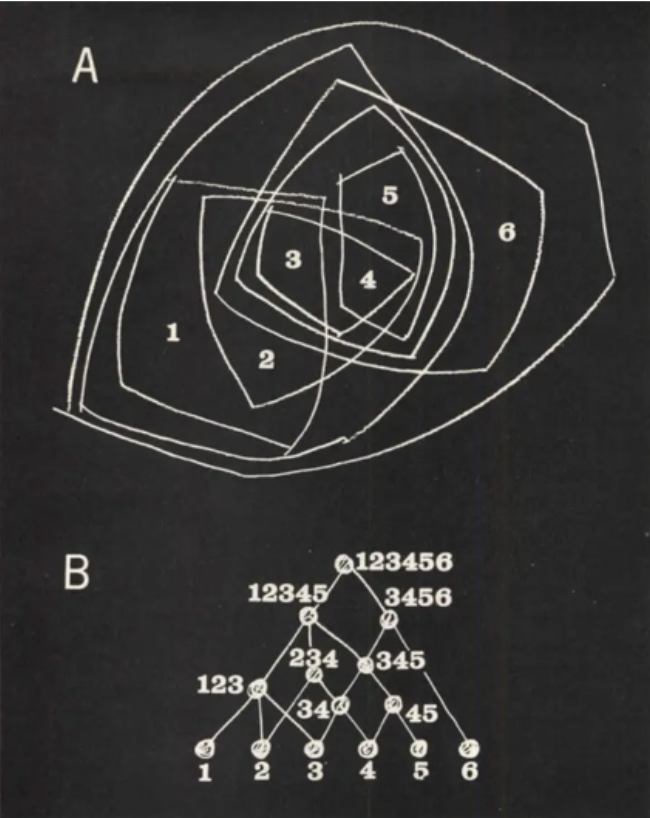

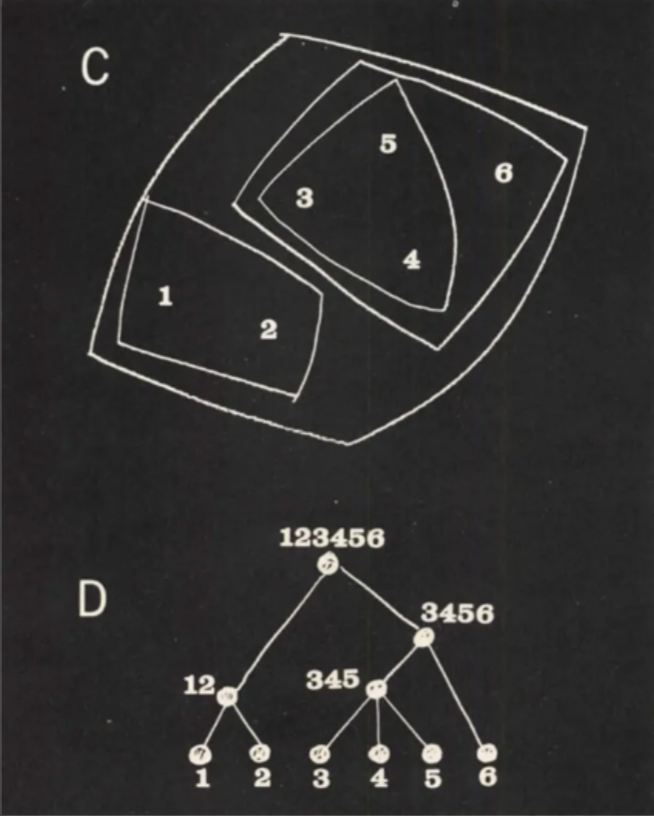

Alexander’s early critiques of modernist urban planning, most notably in his 1965 essay A City is Not a Tree, focused on the concept of ‘scales of relationships’, a concern that defined his career and remains pressing today. The work criticised planners’ tendency to create relationships only between a node and its parent node, like a tree, where Alexander argued that the city is more like a lattice, with multiple relationships between many nodes.

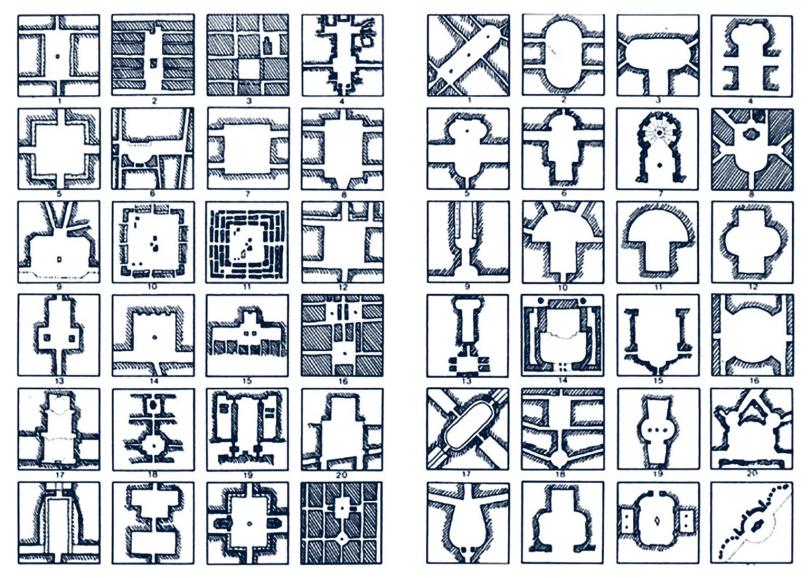

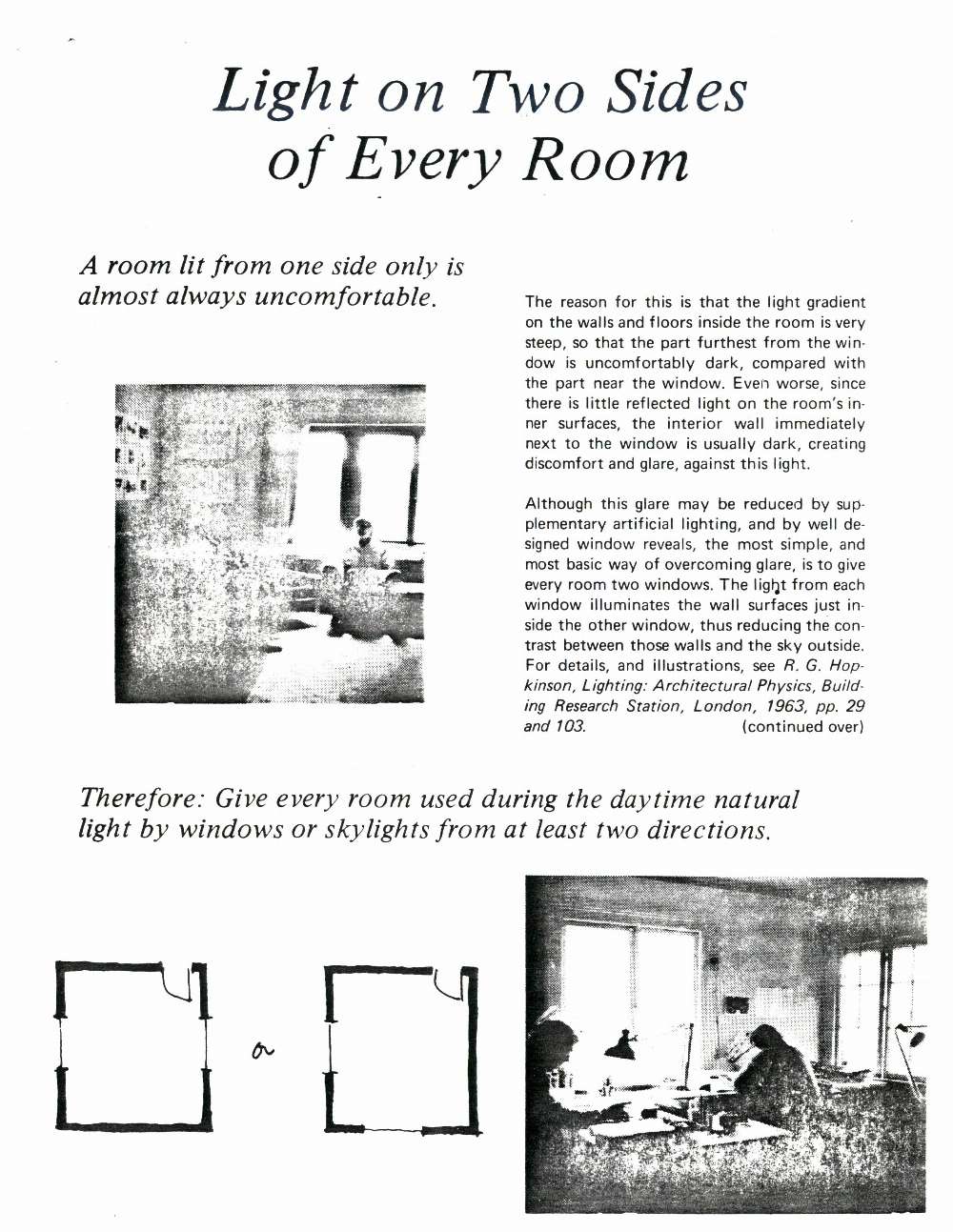

His influence is most famously encapsulated in his 1977 book A Pattern Language. This book presents 253 patterns for designing spaces, ranging from the arrangement of rooms to the structure of entire towns. Each pattern is a spatial abstraction that acts as a lexicon of a belief system, with simple yet profound suggestions such as: every room should have windows on two sides, or each community should have a gathering place. The book’s non-linear format allows readers to explore these patterns in any sequence, nesting multiple scales into a practical and paradigmatic design manual for people to use in creating their own spaces and communities. The maxims in A Pattern Language are endlessly buildable, looking at examples from the past to build the architecture of the future.

The profound impact of this democratic take on urbanism was especially felt in Alexander’s critique of high modernism’s top-down planning approaches. In contrast to the rigid, large-scale designs of modernist architects, Alexander advocated for a more incremental, human-centric model of urban development. His ideas, such as scaling design from the room to the city, helped shape the foundations of New Urbanism in the 1980s and 1990s, which aimed to create walkable neighbourhoods as a correction to urban sprawl. Alexander emphasised the importance of smaller, community-focused spaces, reflecting his belief that the heart of any successful urban space lies in fostering positive human interactions.

Today, Alexander’s work remains vital for architects and urban planners. While some have dismissed his ideas as unfit for the mega-cities of today, it is even more crucial that we redeem a human and neighbourhood scale within our impersonal megalopolises. Alexander’s principles of incremental growth, community involvement and the need to honour architectural heritage serve as a reminder that good architecture is not just about aesthetics but about creating a foundation for scales of human relationships: from the one-to-one, to the family scale, to the neighbourhood or village scale. In an era of rapid urbanisation, Alexander’s ideas are a reminder of the importance of architectural humanism.

Photo Credit: A City Is Not a Tree, A Pattern Language, US Modernist Archives