图片来源: Yip Yew Chong

大城市的公共艺术常被视作美化工程。人们设立雕像、壁画与雕塑来装饰广场空间、柔化水泥与钢筋交织的景观,并纪念历史。然而,当公共艺术仅被视为装饰品,便失去了最核心的功能——创造公共空间。真正的公共艺术不仅要在城市中占一席位,更要积极塑造人们体验、争取和忆记城市空间的方式。

在快速城市化的东南亚城市中,挑战不仅在于要将艺术融入城市总体规划,更要在过程中保留自发性和公民主人翁意识。由谁决定哪种艺术属于公共空间?在政府具备严格规划框架的城市中,实验性与社区主导的艺术介入能否带来真正的影响?

有些倡议证明可以,前提是政府机构与城市规划者明白公共艺术不仅是塑造国家形象的工具。以吉隆坡的民间自发团体RakanKL为例,他们主张保育文化遗产与平衡发展。比起把文化遗产视为博物馆展品,他们选择发起城市漫步、音乐演出和快闪展览,维护公众认识城市和在此生活的权利。他们特别选择无需消费的方式,证明无需花费也可体验城市生活。这类艺术介入虽然短暂,却能产生深远影响,让人们持续反思他们与城市空间的关系。

雅加达的知识共享平台Gudskul打破了公共艺术、教育与社区建筑之间的传统藩篱。比起把艺术视作城市肌理中的静态物品,它选择以集体主义、资源共享和没有等级的知识交换为核心,化身成与别不同的生态系统,与东南亚诸多自上而下的公共艺术计划形成鲜明对比。Gudskul鼓励朋辈间互相学习和集体治理,展示出公共艺术不仅是在城市中陈列艺术品,更是构建蕴含人文关怀、自主权与公民想象力的基础设施。

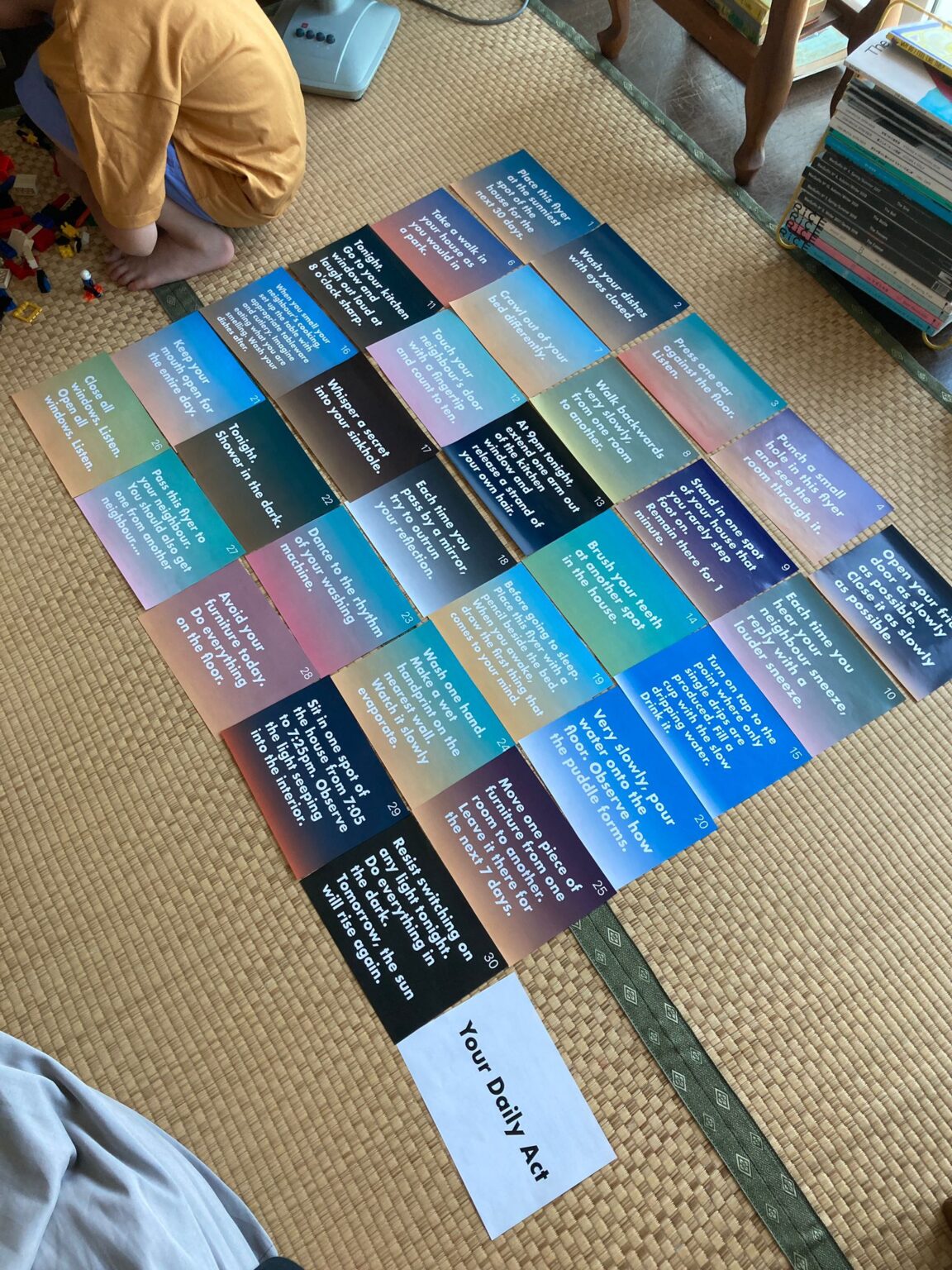

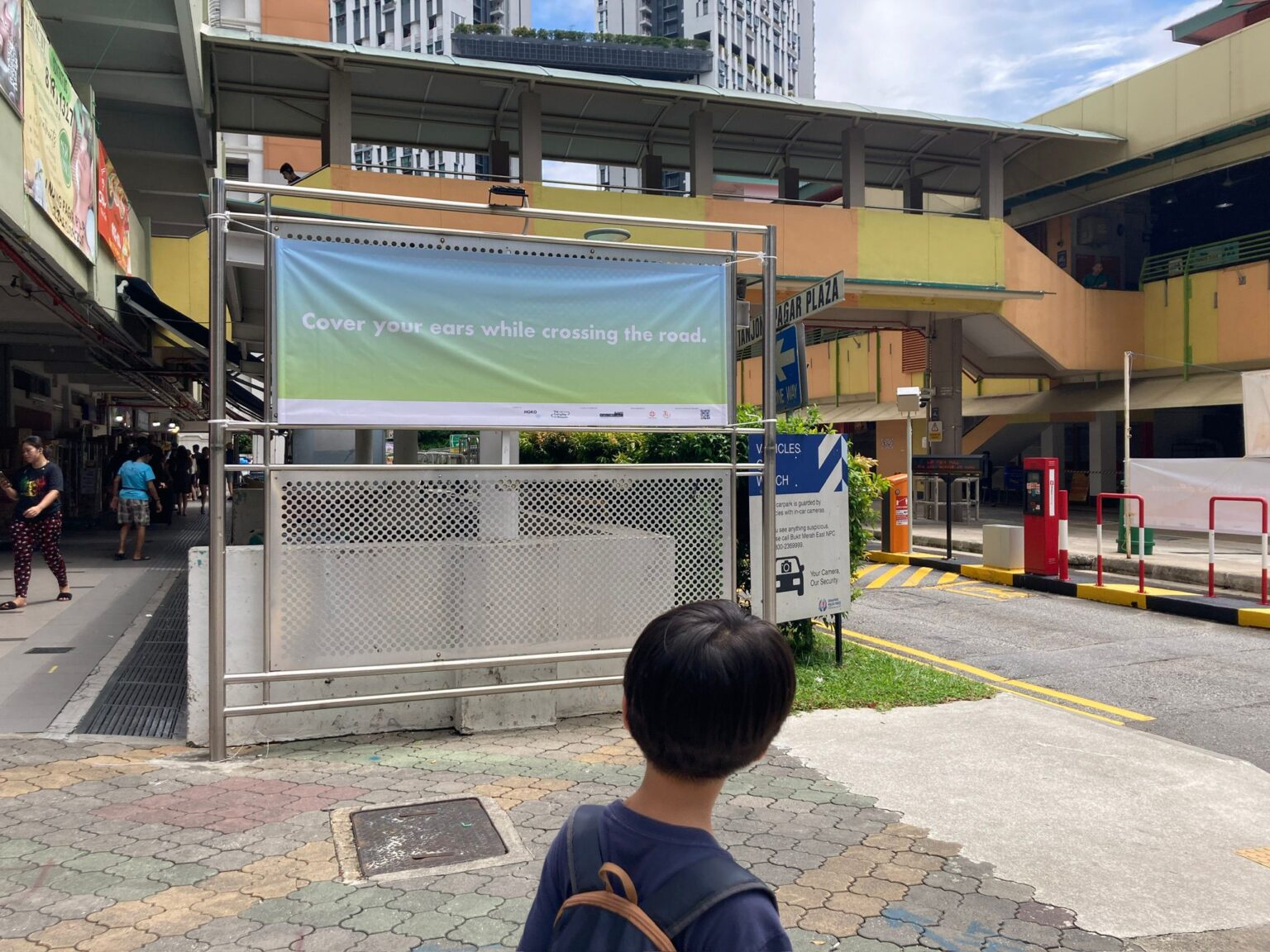

新加坡国家艺术理事会为公共艺术订立了更明确的指导原则和集资途径,其框架注重品质与持久性。部分艺术品如叶耀宗(Yip Yew Chong)的怀旧壁画获得高度评价,其他艺术品如Atelier Hoko的命题式作品,评价则褒贬不一。

城市若想孕育有意义的公共艺术,就不能再视之为街景中的静态装饰。我们要把艺术纳入城市规划,在开放的过程中允许即兴创作、公众参与和讨论,而非视之为最终的点缀。真正的公共艺术理应属于人民。