图片来源: Rivan Awal Lingga

雅加达前首长钟万学在执政期间大兴土木,留下不少大型建筑,当中儿童友好综合公共空间(RPTRA)是政府计划在全雅加达建造300个公共设施的项目。这个项目有个有趣的地方,就是选址。钟万学放弃一些策略性地点,进而利用低收入民居和贫民区附近的闲置土地,希望设施能为社区赋权,帮助改善生活条件,创造更宜居的环境。

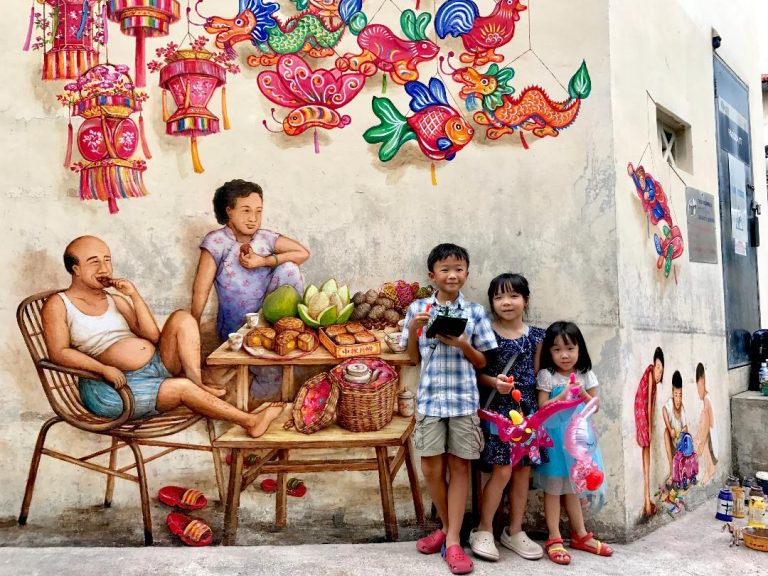

姻缘河儿童友好综合公共空间是第一批落成的设施,其城市脉络吸引了广大民众注意。姻缘河位于雅加达北部,历来夜生活繁盛,是著名的红灯区。这里也是重要的文化地点,雅加达华裔社群每逢扒船节(Peh Cun)就会在这里举行龙舟竞渡。扒船节是水上节庆,在印尼政府于1958年禁止庆祝华族节日前,华裔社区的年轻人会到红溪河划龙舟应节。扒船节会以缘分配对仪式作结,也是由当地地名衍生而成,呼应Cari Jodoh在印尼语的“配对” 意思。

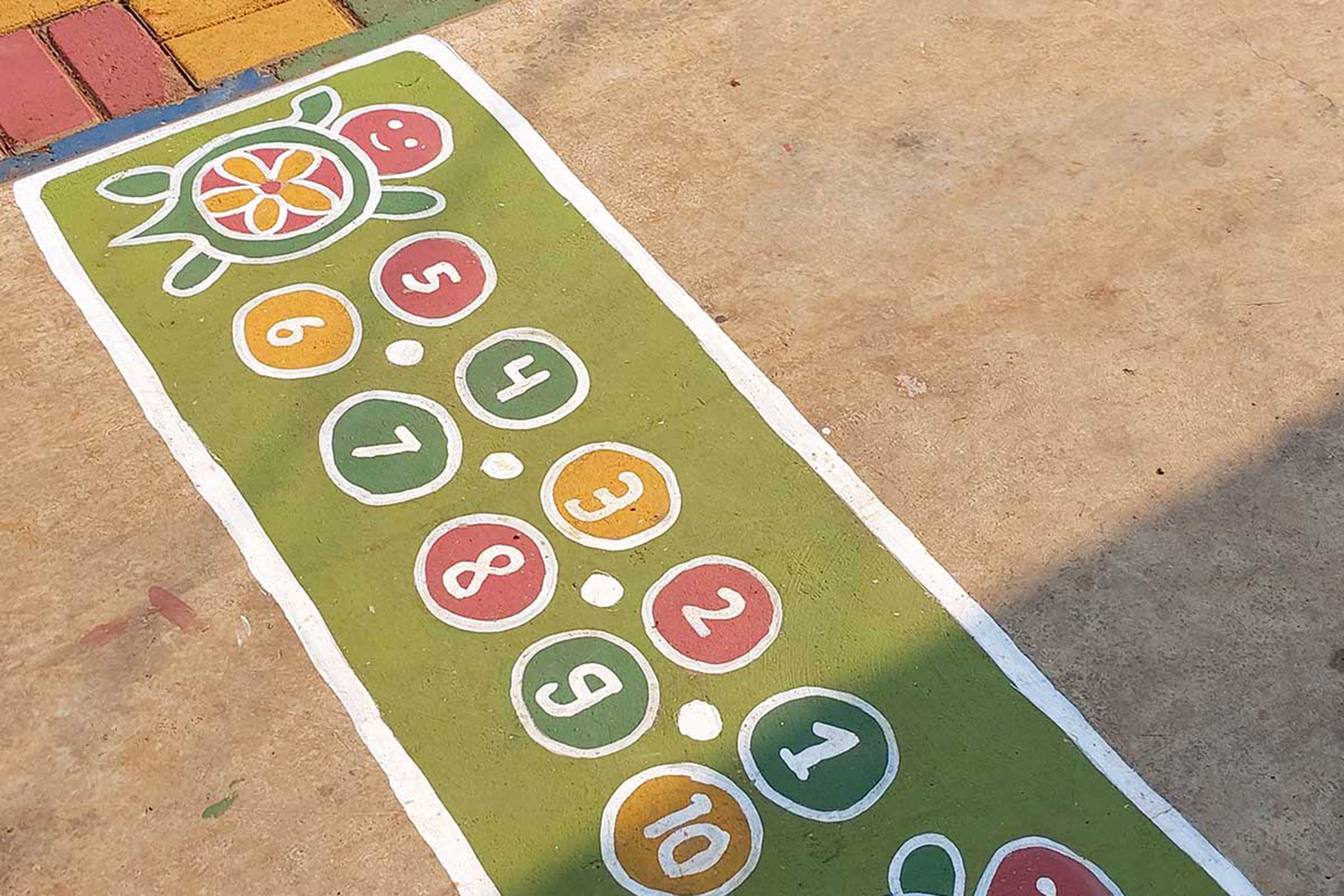

雅加达政府扫荡红灯区后,钟万学提出在姻缘河发展RPTRA项目,由当地公司透过企业社会责任捐献资金,印尼著名建筑师Yori Antar和Tan Tik Lam共同策划,把原址活化,建造多姿多彩的公共空间和儿童游乐场。

他们刻意设计得简单直接。Antar指采用这个取向是为了创造低调的建筑形态,隐去结构元素,以凸显广场和游乐场。空间坐落于河畔的三角地带,当中以纤长钢柱支撑的平顶最为突出,让空间保持开扬、免于封闭。滑板公园和广场则是焦点所在,缔造热闹包容的城市空间。

然而,现时姻缘河儿童友好综合公共空间面临维护问题,设施遭受破坏,加上计划后劲不继,令人关注这里长远能否持续下去。雅加达的问题不是孤例,首尔清溪广场、纽约高架公园等类似的公共空间也面对活力不足的问题,但有赖社群主动参与、有系统的资助和机构管理稳健,这些空间仍能顺利运营。要确保姻缘河等同类空间能维持朝气,雅加达政府或可以向其他例子借鉴,鼓励当地商户和社群参与维护空间,同时定期举办文康活动,让公营和私营机构加强各方面的合作,对维系这类别具意义的城市空间可谓不可或缺。